Looking for the navigator named “Wilf”

For a brief moment, my father, at age 90, once again, saw the image of a smoking Lancaster in a field, in July 1944. I decided to investigate the backstory of the wreckage, with just one precise clue : the location of the plane.

On December 10, 1922, the Gore Park Cenotaph was inaugurated in Hamilton, Ontario. This monument is in honour of the region’s soldiers who died in combat over the years. As this monument does not have inscriptions of names, to find a specific person, it is necessary to consult the roll of honor at the local public library. This record : “We are the Dead”, is updated with each new conflict Canadian soldiers of this region participate.

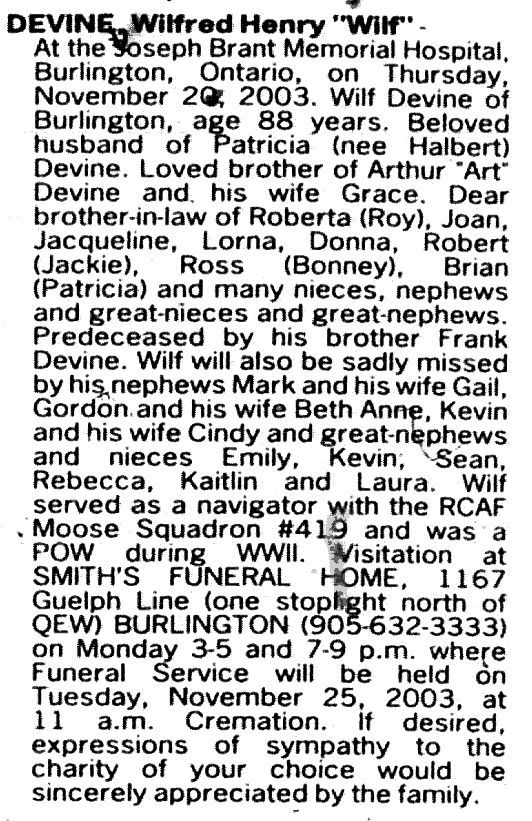

The name of Wilfred Henry Devine (known as Wilf) with his regimental number, is classified among those who gave their lives in sacrifice during the Second World War.

September 3, 1939: Hitler refuses to withdraw from Poland which he invaded 2 days earlier. France and Great Britain declare war on Germany.

September 10, 1939: Canada enters the war, alongside Britan, and the other countries in the British Commonwealth.

1943. Wilf registered to enter the Canadian Air Force (RCAF) as a recruit, and is awaits his admission confirmation. What motivates this Canadian to enlist ?

The fact that he is already 28 years old, makes him unique. He is certainly already established in life path as would be typical in that time period, and at that age.

Romanticism adorns RCAF recruitment posters of the era. Typical images show goggles raised over leather helmets, dressed in a sheepskin jackets, heads tilted towards a cloudy sky crossed by a flight of bombers. The aviator’s mind is invaded by the solemn thought : « I’ll be with you, boys ».

Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, McGill University Libraries, Montreal.

Could we have caught Wilf daydreaming in front of this poster? Captivated by the call to join these patriotic heroes, where freedom merges with courage, happiness and camaraderie? Is this the existential moment in which he had a vision of his duty and therefore his destiny ?

“If I don’t do this, I’m going to miss out on my life.”

There are also the more banal versions, those which convey the things of life, a sentimental break-up, the bitter taste of an insignificant existence which forces one to desire another perspective. And if in the end, it is an opportunity to make one’s dream of flying come true. At this time, there were undoubtably numerous noisy and impressive four-engine aircraft in Ontario airspace to awaken one’s passions. Between 1940 and 1945, the Allies sent 131,000 aircrew members to train in this region of Canada.

« For a really adventurous life, be trained as an aviator, openings are now awaiting sound young men »

There are many studies of the reasons why young men choose to join the air force during wartime.

During the First World War, the « aces », warm-hearted on the ground, became ruthless, skilful and heroes in the air. Above all, solitary heroes crowned with glory, know as the “knights of the sky”. Gradually, with the international development of civil aviation and the great raids of the aeropostale, heroism became a collective enterprise.

And what about patriotism?

An enlightening doctoral thesis on this subject, focusing on Greek pilots during the two world wars, is available here. The author gives an excellent definition of heroic patriotism: « voluntary offering, at the risk of one’s own human life through valiant acts, in favor of the ideal of the fatherland perceived as superior ».

Statistics on the frequency of key words representing patriotic values, used in the aviators’ stories, conclude the thesis. The results are significant: the words heroism and courage are the most frequently cited, and in contrast, rarely national pride.

In today’s world, patriotism is felt above all as a necessary minimum duty, but in the most developed countries, the State is gradually becoming a life insurance policy for the individual.

Even more brutal is this quotation from Marx & Engels: « The bourgeois world has drowned the sacred thrills (religion, chivalric enthusiasm, sentiment) under the icy waters of selfish calculation ».

But for our airmen in wartime, and still for some people today, is the fatherland, that supreme good, like the family, religion and ideology for others, the pretext for one day bringing out of the shadows of the mind ? The desire to tame death by provoking it?

When we begin to wonder why heroism exists, shouldn’t we abandon the rationale ? Except to note that it is not a forced act.

For Freud, the hero is a representation in the unconscious, the perfect identity of « the man who stands up to his father, to overtake and ultimately defeat him ». He also « refuses to give personal life the same value as certain abstract goods ».

Also, « The condition of the warrior is synonymous with the beauty and serenity of the warrior », and this reminds us of the pictorial representations of young men on recruitment posters.

Why ?

The tensions and impulses of the fighter, and his active relationship with death, must not be suggested…

Wilf is accepted into the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan, and joins the Toronto depot for training.

Imagine the activity of this composite beehive, with students from all walks of life mixing with civilian and military instructors and personnel. Recruits were trained in military discipline, weapons drills and maneuvers, while at the same time, learning the fundamentals of aviation and even English for French speakers.

Wilf graduates as an airman second class, and is selected for training to become a flight crew member.. He was to follow the full ten-week preparatory course, already included in the best of the best, as opposed to the lighter program for future wireless operators and gunners.

But if he dreamed of being a pilot, was the fact that he was a math whiz lucky for Wilf ? To find out, we’d need to know his results on the « Link Trainer » flight simulator. This fearsome machine measured an aspirant’s ability to fly a plane, testing his skill and reflexes.

The result was that he was not retained as a pilot. His aptitude for rigorously processing numerical and geometric data decided otherwise, and he was sent to an Air Observer School for a further 22 weeks. He finally flew over twenty hours to practice bombing techniques, and completed his specialization with four intensive weeks of training in new electronic navigation techniques.

The future Canadian airmen will all be attached to the Royal Air Force Bomber Command in the UK, and would operate mainly at night.

The first Avro-Lancaster bombers were equipped with a transparent hemispherical dome installed in the cabin roof, for 360-degree observation of the horizon. Since terrestrial references were non-existent at night, the navigator found his course by referring to the stars with a sextant. However, this method was vulnerable to the sudden winds at altitude, which caused the plane to drift.

By the time Wilf started learning astronavigation, radionavigation systems were reliable and operational.

July 1944

World war has never been so aptly named, and on the 25th of July in Berlin, Goebbels was appointed Reich Plenipotentiary for Total War, and vacations are prohibited by decree for all workers whose activity is related to the war.

De Gaulle may have been received in Washington by Roosevelt, and obtained official recognition of his provisional government, but the Allied armies in France, now a million strong, are only at Caen. German defensive lines had forced the mostly American troops to cross the hedged Normandy bocage, and the advance was very slow and costly in terms of human lives.

On the Eastern Front, the Soviets were blocked in Estonia, and the Red Army suffered a costly defeat in Finland.

Meanwhile, in the Pacific, the Americans set up a new air base on each island they conquered, but Japanese resistance was fierce, casualties high, even to hold on to a tiny atoll.

In the air, the RCAF and RAF resumed operations in German skies. They were no longer occupied with the tactical support of infantry on French soil, as they had been during the D-Day landings.

Since 1942, when the new Marshal Arthur Travers Harris was appointed Commander-in-Chief of Bomber Command, air operations over Germany have changed in nature and intensity, becoming known as strategic bombing.

The justification for these giant raids is the destruction of the Reich’s military and industrial infrastructures, and vital communications nodes. These tactics made it nearly impossible to avoiding collateral damage in the form of horrific casualties among the civilian population.

But « Bomber Harris » was soon nicknamed « Butcher Harris », and his favorite proverb, « He who sows the wind reaps the whirlwind », clearly illustrates the vindictive nature of these bombing raids. Already in 1943, a series of raids in the Ruhr and Hamburg killed 40,000 civilians. The target « military-industrial complex in a densely populated area » sometimes in fact defined the entire city as the main objective. This was evidenced by one report: « most municipal and cultural buildings were destroyed ». The theory behind strategic bombing is indeed to break down the war effort and the morale of the population, but its effectiveness ultimately proved to be controversial and unclear. In December 1944, military equipment was still being produced in Germany, and a new sixth SS army with brand-new armor was created, enabling Hitler to launch the Battle of the Bulge.

July 24, 1944.

The Americans conceived an operation, with massive air support, to destroy the German lines south of the English Channel, blocking access to Brittany and Paris. Operation Cobra was interrupted as soon as it began, due to bad weather, and 150 soldiers including a general were killed by bombs dropped by the United States Army Forces.

Bomber Command decided to launch a series of raids on Stuttgart, a rail hub and industrial center with factories including Bosch, Daimler-Benz and SKF.

Flight sergeant (F/S > senior non-commissioned officer) Wilf is now a member of the 419 squadron (sq) « Moose », based at Middleton St George in the north of England, and crew navigator for F/S Jack Albert Phillis (23), a native of Missouri in the USA. Phillis, who enlisted in 1942, took command of Avro-Lancaster X N°KB719 after his « second Dickie operation » on May 31, his first and last raid as a « sprog » (student pilot) at the controls.

This new crew of six, including Wilf, successfully carried out their first mission… on D-Day over Coutances ! On the way back, pilot officer (P/O > junior officer) rear gunner John Patrick Shortt (20), known as « Shorty » and originally from Vancouver, fired his first 200 rounds to defend the aircraft. The following night, Shorty and center turret gunner P/O John Ellard Searson (19), nicknamed « Johnny », fire on a Luftwaffe Junkers fighter-bomber in Achères, a marshalling yard near Paris. By July 24, the crew had carried out a total of 9 operations, and on several other occasions were involved in combat or managed to evade the enemy. The July 4 mission to the Villeneuve-Saint-Georges marshalling yard could have proved fatal, as a German fighter disabled the starboard engine and punctured the fuselage and fuel tank. Phillis, despite the malfunctions and thanks to the assistance of sergeant flight engineer James Norman, the only British pilot on board, made it to the target and back to Middleton.

The other two P/Os in the crew are Jack Spevak (22) from Ottawa, wireless operator air gunner, and Richard Glanville MacKinnon (19) from British Columbia, « bomb aimer ».

The Lancaster was Bomber Command’s main four-engine bomber, designed by the Avro company, and 7,400 of them were produced. It could carry three times the bomb load of similar aircraft of its day, and up to ten tons.

Starting at the nose of the fuselage, we find the bomber’s station, where he lies face down in front of a transparent Plexiglas dome, to aim and drop the explosive charges when the time comes. The rest of the time, he’s stationed at the controls of two cannons in a turret mounted above. In the upper section, on the roof of the bomb bay, there are four crew members: at the front, the pilot and mechanic sit side by side, and behind a curtain, the navigator and radio operator. Two-thirds of the way up the nose and at the end of the bomb bay, the top gunner handles his two guns, in a turret offering a 360-degree view. Finally, at the far end of the fuselage, the rear gunner occupies the smallest space in the aircraft.

The Lancaster’s 31-meter wingspan was designed to create the lift needed at high altitude, a flying practice that protects bombers from the enemy, but leaves men vulnerable to the cold and lack of oxygen. Missions within a maximum range of 2,700 km lasted a minimum of eight hours, with particularly long outward journeys at a speed reduced from the normal 450km/h to 100km/h, the aircraft weighed down with bombs and fuel. At the cruising altitude of 6,000 meters, the Lancaster passes through rarefied air at -30°C, and airtightness, unlike structural strength, is not a manufacturing priority in view of the intense aircraft production rates required.

Thanks to the heater in the cockpit, the temperature is bearable for the four men inside. As the two turrets still communicate with the cabin, the bomber and gunner above receive some of the hot air, but as soon as the rear gunner closes the sliding door of his turret, he is isolated, connected to the others by an intercom.

In addition to thermal underwear, he’s issued with a flexible suit covered with heating resistors, which he covers with sweaters and thick lined gabardine. He has a pair of electric gloves under his leather gloves, also powered by the plane’s batteries, in the hope of avoiding frostbite. Despite the multi-layered clothing technique, many gunners suffered from pneumonia.

July 24, 1944: 8:00 a.m.

Gunsmiths fill carts with bombs and cannon ammunition. Refuelling begins, and other mechanics work on the planes until just a few minutes before take-off.

The female staff of the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force also got involved, preparing outfits, parachutes, food rations and thermos flasks.

The crews don’t know that it’s going to be a long day, as the briefing doesn’t take place until late afternoon.

July 24, 1944: 5:00 p.m.

When the captain pulls back the curtain to reveal the target as Stuttgart, at 1000km it is the furthest many have flown.

As usual, the briefing starts with the flight plan and weather forecast, followed by tactics and the level of defenses in this part of Baden-Württemberg and on the overall flight path.

But on this day, the crews appear to have been told that some key information was delayed from Bomber Command, and was expected to be passed on to them at the last moment.

It’s an uncomfortable situation for Wilf, as he’ll be working alone with his map after the briefing is completed.

We refuel the last plane at the end of the evening, and everyone relaxes at the pre-operational meal.

Then the 15 crews of the 419sq collect their flight equipment, evacuation kits and parachutes.

July 24, 1944: 9:33pm (UK time)

At last!

The KB719 bomber takes off, first circling for 45 minutes to gain altitude, as it is so heavy. It later became part of a « stream » of 460 Lancasters and 153 Halifaxes, flying over London, Dieppe and Orléans, before turning due east toward Stuttgart.

Weather and visibility were mediocre, with the bombers reaching a ceiling of just 5600 meters, and the winds proving to be different from the initial forecasts. Many were flying in an « S » pattern, moving away from each other to avoid the potential to collide.

Today’s raid report from the « Operation Record Book » is short but revealing: « This was the first very long trip for some crews, and with the tactics employed, some difficulties were encountered…Ground training was carried out as far as possible ».

But even more intractable are the figures: the death toll from these three series of raids was very high, with 21 bombers never returning from the first raid alone.

In fact, an air attack on Stuttgart in 1944 is the most perilous thing to accomplish, and Wilf and the others don’t have much information regarding the dangers of this target and mission available. The German authorities considered this city so safe at the time, that it sheltered refugees from other destroyed cities.

If there’s one disastrous impact of strategic bombing for the Reich, it’s that a large proportion of gun production is devoted to air defense, depriving other sectors of these resources. Stuttgart, for example, was defended by 49 gun batteries guided by radar and information from several observation towers, and by a fighter base to the south of the city.

July 25, 1944: 0:00 a.m.

Above the city, they see the reflections of thousands of aluminum strips, decoys released by other Lancasters themselves used as bait, producing false echoes on enemy radars.

On the ground, searchlights intermittently sweep the skies, and the barrage of « Flak » shells fired by the German air defense system (Flugabwehrkanone) increases in intensity. Even more dangerous were the glowing corridors of light – chains of flares released over the bombers by enemy Junkers.

Phillis now enters the area marked by the bomb sight, and marked by the target indicators released by the pathfinder, Mac Kinnon opens the bomb bay doors.

The hundreds of tons of explosive and incendiary shells from these raids caused the most devastating damage the city had ever suffered, resulting in the deaths of over a thousand people.

After delivering their bombs, the Lancaster gradually turns west for the return trip.

He took off during the night at the controls of his Junkers 88-G, and had already shot down a four-engine aircraft near Strasbourg, which he calls « Viermot » because he could not identify the model.

Silesia-born haupmann (captain) Paul Zorner (24) has added another trophy to his trophy cabinet, which now totals 57. For the past few months, he had been commanding a group from Unit III of the « Nachtjagd » 5 (fifth night fighter squadron) based at Laon in the Aisne region of France. The special version of his aircraft is equipped with a Naxos Z, a radar that guides it inevitably towards the Allied bombers at a speed of 100 km per hour faster. Not only is he an ace pilot and marksman, he also possesses exceptional orientation and navigation skills, matching those of his on-board radar operator.

He knew the routes taken by the bomber fleets back to England, and set a course north-west for Strasbourg. Skirting Luxembourg, the radar detects a four-engined aircraft, and the clouds of this moonless night allow him to attack his prey by surprise. His speciality is to approach at maximum speed, sometimes to less than a hundred meters, to make the decision to shoot at the final moment.

This tactic, even if Zorner is spotted, mitigates the risk of being targeted by the Lancaster’s cannon, and should make it impossible for Phillis to « corkscrew », slowing down abruptly, then turning in a dive and dropping a flash bomb that blinds the fighter pilot.

This tactic, even if Zorner is spotted, mitigates the risk of being targeted by the Lancaster’s cannon, and should make it impossible for Phillis to « corkscrew », slowing down abruptly, then turning in a dive and dropping a flash bomb that blinds the fighter pilot.

To no avail.

The interception was so swift that none of the crew saw the Junkers. Zorner, navigating by radar in this pea soup, only caught a glimpse of the bomber’s fuselage, but enough to determine in a fraction of a second the trajectory of the rocket he fired, which hit the Lancaster in the Saint-Dizier area.

Jack Spevak is killed by shrapnel.

An intense fire breaks out on board, and Phillis orders the evacuation.

The hatch in the floor of the bomber bay is very narrow, and the engineers tried in vain to enlarge it, but Mac Kinnon successfully ejected through the mouse hole.

Phillis and the only two surviving airmen had to use the hatch above the cockpit. James Norman was the first to exit via the emergency exit, tragicallyf he released his parachute too soon, and the canopy was sucked into an engine.

Phillis jumps to escape the flames in which he can no longer see Wilf, the plane swirls in a dive and becomes almost impossible to identify.

Zorner observed the trail of the burning four-engine aircraft on a south-westerly heading, and located the crash 30km north-west of Saint-Dizier at 2:54 a.m. This time does not correspond to the Phillis time: about 01:30. However, there is absolutely no doubt that KB719 was the only aircraft found in the area, and an investigating officer based his findings on the testimony of local residents indicates 02:00 English time, or 03:00 in France.

The plane flips over and crashes a kilometer from Bassu, a small village in the Marne department.

Phillis, unharmed, lands in a nearby field, hides his parachute, harness and « Mae West », the life jacket named after the actress, in a wood, and decides to stay under the shelter of the forest.

Mac Kinnon is located 40 km west of Châlons-en-Champagne.

As for Wilf?

He managed to eject from the plane at an altitude of 300 metres, and was also hiding not far from Saint-Dizier!

July 25, 1944: 07:00 a.m.

The Lancaster’s fuselage is still smoking, its nose buried in the earth. A Wehrmacht officer authorized the mayor of Bassu, accompanied by some of the local inhabitants, to dig out bodies if they found any. They have already found Norman’s body under the starboard wing, clinging to the lines of his parachute.

In the fuselage, two bodies joined in death, one behind the other : in front, with his curly hair, Jack Spevak, killed in mid-air, then John Searson.

The center gunner had to leave his turret and use the rear door as an escape route. Sucked in by gravity, John Searson was undoubtedly unable to climb the five meters to the door due to the excessive g forces of the dive.

About a kilometer further on, locals find the Lancaster’s tail torn off, and in the turret the body of John Patrick Shortt. The unfortunate rear gunner would have had to go to the door to attach himself to the parachute clipped on for him. It was impossible to position himself at the guns with a parachute, due to the lack of space in the rear turret.

July 25, 1944: 08:00 a.m.

A farmer discovers a parachute in the woods, then Phillis in his hideout. The man tells him to stay where he is, and joins him accompanied by Gaston Chappat de Bassu, who takes him in at his house.

The next day, Phillis undergoes a routine interrogation by Resistance lieutenant « Petit » from Vitry-le François. The next day, a police officer drew his portrait to produce an identity card, work permit and bicycle license. He also gets civilian clothes and 4,000 francs.

Since 1941, resistance networks (as opposed to « movements ») have been organized to exfiltrate Allied servicemen. The process was long, dangerous, and the « clients » numerous.

For the past three days, Mac Kinnon had been hiding by day and walking by night in the direction of Châlons-en-Champagne. So far, he had only met a lumberjack who told him that the Germans had abandoned the search for the three survivors of the crash, when a farmer offered him food and lodging.

July 31, 1944

Phillis leaves Chappat and Bassu on his motorcycle to go to Petit’s house. By bike, accompanied by the daughter and a friend, they go as far as Saint-Dizier, to a wine cellar. From there, they take a cab to Chaumont.

Mac Kinnon found new lodgings each night, until he was guided to the home of a Resistance fighter in the village of Soudron, in the west of France. This village was equidistant from Vitry-le-François and Châlons-en-Champagne. He stayed there until August 28, 1944.

August 1, 1944

At 9.00 am, Petit and Phillis cycled to a village near Chaumont. Here they ate a meal at a wine wholesaler’s, who subsequently drove them to Dijon where they remained for the night.

August 2, 1944

A long 100km stage by bike followed the next day to Tournus, where Phillis and Petit stayed for three further days.

August 6, 1944

Arriving by Taxi in Lugny, Petit parted company with Phillis to return to Vitry-le-François (now 300km to the north). Before leaving, he introduced the pilote to the Resistance leader of a maquis in « Tournegeois », the region between Mâcon and Chalon-sur-Saône.

They joined the Maquis camp in a forest near Lugny, a dangerous little town with a Wehrmacht garrison in the village hall and commanding officer based in the castle.

August 7, 1944

Later, a report by investigating officer W.J. Shaw mentions that, after the Lancaster crash, the local authorities in Bassu claimed that one airman had been taken in by Mr. Chappat of Bassu. This fact was verified by Phillis. It was stated that two other airmen were hidden by Mr. Collard of Vitry-le-François, this we know to be inaccurate from Mac Kinnon’s autobiographical account.

If we accept the hypothesis that Mr. Collard hid Wilf after July 25, a short testimony from the Resistance suggests a plausible alternative theory. Wilf could have been lodged until that day with Georges Vaucouleur (22), a native of Vitry-le-François, who was cited after the war for « services rendered for acts of resistance » recognized by the French state.

On August 7, Wilf left to join the « Garnier » maquis, based at the « Chalet des Gaudes » under the command of Georges Debert, in the Mathons forest 40 kilometers south of Saint-Dizier.

The reason is logical, this group of some 30 men included other airmen who survived bombing raids between July 14 and 19: F/S Norman Oates (RAF), Sergeant George Armstrong Alexander (RAF), F/S Stanley Robert Ashton and Ernest Harold Wells (RCAF), F/Lieutenant K.Stevens (RAF), and (subject to confirmation) F/S John Charles Wellein (RCAF) and Sergeant W.G Barlow (RAF).

This maquis had salvaged weapons, including two aircraft machine guns, and was supplied by the Douillot family from the Bonshommes farm.

Even though the Resistance fighters were an auxiliary force for the regular army, used especially effectively to protect the bridges, many young men were won over by the euphoria of the landings, and unfortunately paid for it with their lives. This came despite De Gaulle’s instructions: « …Do not expose your lives unnecessarily: wait for the hour when I will give you the signal to stand up and strike the enemy… ». This was particularly true during the most ferocious period of Nazi repression in the summer of 1944.

August 10, 1944

At around 4 a.m., more than a thousand German soldiers attacked the maquis, and the resistance fighters split into two groups: Chief Debert’s group escaped to the south, while part of the other group retreated to the north after a heavy firefight. The other group remained, made up of Gabriel Sanrey (23), Maurice Launois (26), René Jakubas (18) and Serge Dervaire (17), as well as our airmen. Sanrey is dressed as a forest ranger, and tries in vain to explain that they are woodcutters who have come to work, but the four maquisards are executed on the spot. It was dark time of the war, as the Allied forces approached, that was marked by such massacres by the Nazis. The next day, soldiers returned to loot and set fire to the Douillot’s farm, killing their child (aged 11) who had escaped.

Wilf and the other airmen are arrested.

August 16, 1944

Phillis leaves the Lugny maquis to stay at Château Bellecroix in Chagny, where he meets five other servicemen, three American and two British.

August 27, 1944

Along with American Lieutenant Bill Schade (USAAF), Phillis returned to hide out at the Maquis camp at Lugny.

August 28, 1944

Mac Kinnon joins the maquis in the Soudron forest, where he meets Scottish war reporter Alexandre Gault Mac Gowan. After covering the campaigns in North Africa and Italy, Mac Gowan was in France on D-Day, machine-gunned aboard a jeep on August 15 by two German light tanks, and arrested unhurt. He’s in the Soudron forest because he escaped, improbably, by jumping from a prisoner train in the middle of the night.

August 29, 1944

Patton’s American soldiers liberated the ruins of Châlons-en-Champagne, and Mac Kinnon was repatriated, likely via the UK.

August 31, 1944

Phillis and Schade are taken to a Resistance airfield, to fly to the UK.

The story of POW (Prisonner Of War) W.H.Devine

(Based on other prisoners’ testimonies, historians’ studies and my research)

August 10, 1944 (return)

With 20 days to spare, Wilf would have been present at the liberation of Saint-Dizier.

After several gatherings in unsanitary camps for sorting purposes, and exhausting walks on an empty stomach, he was transported on a freight train to Stalag Luft VII in Bakau, now Bąków in south-west Poland (near Kluczbork).

The term « Stalag » (Stammlager) refers to the main prisoner-of-war camp, and « Luft » to the camp reserved for captured airmen, guarded and administered by the Lutwaffe, the German air force. VII is located in Silesia, occupied Poland, some 100km from Wroclaw, 400km from Dresden and 1500km from Paris. It was opened in June 1944 and closed in January 1945, built to hold over 4,000 men, but the last prisoner was only numbered 1358.

August 22, 1944

A new group of arriving prisoners, 2/3 of whom are Bomber Command crews, is referred to as a « troop », and today’s troop, number 27, is made up of 109 men. Numbers 25 and 26 are dated August 14 and 15 respectively.

F/S William Ernest Egri (RCAF) and Norman Oates (captured at Mathons with Wilf) of the 27, have prisoner numbers 574 and 614. Thus, the probability of Wilf’s first day of internment as August 22 is very high, with his prisoner number recorded as 570.

F/S Oates : « My food is a daily bowl of sugar beet pulp boiled with a piece of potato ». The tone of the statement by Albert Kadler, a Swiss visitor with the identical function of a Red Cross observer, is more optimistic: « The site is pleasant, well chosen and offers excellent views ».

In the barracks, there were no beds and no heating, just straw mattresses on wooden floors. The latrines, which could be used as escape tunnels, are located far from the high barbed-wire fence encircling the camps. There is a water pump in the center.

In the thirty weeks of the Stalag’s existence, there were no extraordinary events, such as the spectacular escape from Stalag Luft III, to inspire Hollywood. On December 27, they mourned the death of Sergeant Stevenson, mistakenly shot by a guard.

The day begins with roll call in the morning, and from time to time the soldiers carry out thorough searches of the barracks. Football is played a lot, and in the evenings there are recitals of classical music on gramophone records, dice-throwing and other bowling games, and boxing matches.

Like Wilf, 70% of them were victims of a Nachtjagd hunter, and they tell each other about their adventures between Red Cross parcel deliveries.

January 15, 1945

Luft VII was at the center of the Soviet offensive, and air raids were now a daily occurrence. The harsh Silesian winter begins as many Lutwaffe soldiers arrive as reinforcements.

January 19, 1945

It’s snowing.

The prisoners were forced to evacuate the camp at gunpoint, and marched 500 km to Stalag III in Luckenwalde, 50 km south of Berlin.

Advancing through the blizzard, starving and exhausted, they were crammed into barns in the middle of the night.

They meet other prisoners from other camps, abandoned by their guards as unfit to continue with the rest of the column. The soldiers pressed on and were terrified by Russian artillery fire that caused destruction and havoc. They observed fleeing SS soldiers from time to time.

Some escape, going into hiding with other prisoners, working on farms, or even working with the locals. It was dangerours for those who could not prove their identity, as often Russian soldiers, emerging from T34 tanks, tended to suspect virtually everyone.

Monday, February 5, 1945

In the midst of other convoys full of wounded soldiers, a train awaits them at Goldberg Yard. At 55 prisoners per car, many of them suffering from dysentery, with no toilet facilities or drinking water.

February 9, 1945

Wilf and the others from Luft VII arrived the day before at the gigantic Stalag III-A 52 km south of Berlin near Luckenwalde. It was now filled with 38,000 captives, as part of the 12,000 contingent from all the other evacuated stalags. They were separated from the older prisoners and housed in 400-seat barracks. A Red Cross delegation gave them a cigarette after a hot shower and minimum medical assistance.This Stalag was synonymous with terror, especially in the compound where 4,000 Russian prisoners died as a result of inhuman forced labor.

April 12, 1945

But where’s Wilf?

Since February, there have been more deaths, most were victims of disease and exhaustion. Escape attempts were largely forbidden by the prisoners’ representatives, thought to be pointless, when they could observe hundreds of bombers flying past on their way to bomb Berlin nearly continually.

Hundreds of prisoners are transferred by train this day to a Munich Stalag.

April 22, 1945

At 6.00 am, the first Russian tank entered the compound, followed at 10.00 am by many more tanks. The 9,000 Russian captives were freed and went to pillage the town.

May 5, 1945

The Allied prisoners of war are all still interned, but under Russian control, they can still move around freely within the compound. American trucks and ambulances bring in rations, and evacuate the wounded. Many men were demoralized by this surreal situation, and some managed to escape by taking advantage of the chaos, but the Russian guards also would shoot.

May 19, 1945

Russian trucks will transport all the prisoners to the American forces in Dresden. Wilf probably joined thousands of other former prisoners in Operation Exodus. They would have been repatriated by transport plane to Brussels, then on to England.

February 15, 2022

In the archives of « The Canada Gazette » of February 2, 1946, I found a list of airmen integrated into the RCAF Reserve by order-in-council of November 1 of the Canadian Department of National Defense. WH Devine (serial number J92351/POW 570), our Wilf, was on this list.

I contacted the Hamilton Public Library, where he is listed on the Roll of Honour as having died for his country. An archivist by the name of Michelle assisted me and found his obituary in « The Hamilton Spectator » dated November 22, 2003 : Wilf left our eternity on Friday November 20 at the age of 88.

In November 1945, Jack Phillis sent a letter to John Patrick Shortt’s father confirming his son’s death, along with two photos of his grave decorated with flowers by local residents, probably taken by Gaston Chappat, even though the ceremony had been forbidden.

James Norman, Jack Spevak and John Ellard Searson are also buried in the Bassu communal cemetery.

Major Paul Zorner died on January 24, 2014 at the age of 93 in Hombourg.

Saint-Jeannet, March 24 2022

Note: You may note illustration errors in the AI-generated images utilized, in the foregoing document, they reflect technology limitations inherent in the free applications available to me at time of writing.

Bibliographic and digital sources

Maria Coroli :

«Le Patriotisme des pilotes grecs… » Thèse de Doctorat présentée à l’Université Paul-Valéry III Montpellier

Éric Desmons :

« Le pro patria mori et le mystère de l’héroïsme » Quaderni N°62

Centre Juno Beach :

« Le Canada durant la seconde guerre mondiale » junobeach.org

Maxime Tellier :

« 1939-1945 : Londres, Tokyo, Dresde, à l’heure des bombardements massifs » franceculture.fr

The National Archives Kew (Richmond, England) :

Références WO 208/3321/2160 – WO 208/3322/52

419 Squadron.com

Daniel Carville (francecrashes39-45.net)

olivier.housseaux.free.fr

lancaster-archive.com

rafcommands.com

Veterans Affairs Canada (veterans.gc.ca)

BAC (Bibliothèque et Archives Canada – Library and Archives Canada)

stringfixer.com

fandavion.free.fr

Commonwealth war graves commission

International Bomber Command Centre (Lincoln, England)

luftwaffe.cz

Jean-Marie Chirol (Club Mémoires 52)

Oliver Clutton-Brock – Raymond Crompton :

« The Long Road: Trials and Tribulations of Airmen Prisoners from Bankau to Berlin, June 1944–May 1945 » © Grub Street 2013

Bomber Command Museum of Canada :

« RAF Operations Record Book » July 1944

W. R. CHORLEY :

« Bomber Command Losses » Vol.5 (1944) ©Midland Publishing (8 décembre 1997)

Thank’s to Michelle, Team Hamilton Public Library, Local History & Archives